chapter 21

Guam to Japan”

“We who lived in concentration camps can remember the men who walked throughthe huts comforting others, giving away their last piece of bread.” — Viktor E. Frankl

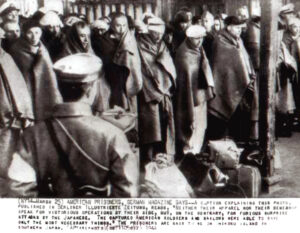

After our capture, we were kept in the church building for a month. Built in the 16th century by the Spanish, it was the only building on the island large enough to hold all the prisoners.

The first day we arrived an interpreter announced that, if any prisoner tried to escape, all of us would be lined up against the wall and executed by firing squad. Hunger gnawed at our insides like a ravenous demon, and fear became our constant companion. Conversations among close friends dwindled to mere grunts as boredom inevitably set in, and each man seemed to shrink into the isolation of his own private hell.

We were fed a tasteless cup of watery stew twice a day, and everyone quickly lost anywhere from 20 to 50 pounds within a few weeks. Japanese guards with bayonets held close to their chests lined every exit, and we were held in a constant state of near starvation, weakness, and paralyzing anxiety.

At the behest of the guards, six outdoor latrines were hastily constructed by the prisoners. We dug a slanted ditch and lined it with tin on all four sides with an opening at the low end. Occasionally, we were permitted to throw buckets of water in the ditch to flush the waste down the hill. Prisoners had to bow to the Japanese guards for permission to stand in the long latrine line. Early on, two men ventured out in the dark to use the latrine without permission, and they were quickly clubbed to death. Afterwards, no one was permitted to go to the bathroom at night. Many of us were unable to hold it all through the night. So, we loosened some planks from the old wood floor to relieve ourselves. Then, we were forced to endure the awful stench of piss all day long.

We weren’t permitted to take a bath or wash our clothes, and the foul stench of unwashed bodies packed together in close quarters grew progressively worse. Our backs were aching stiff from sleeping on wooden floors, benches, and church pews. Bright lights, that were kept on constantly to ensure that we didn’t escape, deprived us of the essential comforts of sleep.

Several times a day they took roll call. It was always preceded by a flurry of activity, as more guards entered the church in a brazen display of power. As they lined us up into individual rows, we often imagined that they were actually lining us up to gun us all down.

A month later, we were loaded onto a Japanese freighter called the “Argentia Maru.” Over 300 men were crammed in the cargo hold of the ship. The air was stale and smelled increasingly like a nauseating combination of vomit and urine. There wasn’t enough room to sit or lie down. Most men remained standing side by side until weakness and exhaustion eventually overcame them. When someone collapsed, they got trampled.

On the ship, they fed us rice and soup twice a day in larger portions than in the Catholic Church. Initially, we were excited at the size of the rice bowls the guards dished up the first day, until we looked down and saw that they were crawling with weevils. The guy next to me was fastidiously and furiously trying to pick the weevils out of his bowl one at a time. The rest of us just stared vacantly at our rice bowls. After a few minutes had passed, seaman first class Wilson shouted, “Hell, that’s fresh meat guys!” and proceeded to wolf the weevils down like movie popcorn. We all stared at him in shocked amazement, and after a long pause somebody started laughing. Then, someone else began laughing. Soon, uproarious laughter had erupted through the entire population of prisoners. The laughter was just the kind of catharsis we needed to be sure. After the laughter finally died down, we ate the rice, weevils and all.

On the ship, they fed us rice and soup twice a day in larger portions than in the Catholic Church. Initially, we were excited at the size of the rice bowls the guards dished up the first day, until we looked down and saw that they were crawling with weevils. The guy next to me was fastidiously and furiously trying to pick the weevils out of his bowl one at a time. The rest of us just stared vacantly at our rice bowls. After a few minutes had passed, seaman first class Wilson shouted, “Hell, that’s fresh meat guys!” and proceeded to wolf the weevils down like movie popcorn. We all stared at him in shocked amazement, and after a long pause somebody started laughing. Then, someone else began laughing. Soon, uproarious laughter had erupted through the entire population of prisoners. The laughter was just the kind of catharsis we needed to be sure. After the laughter finally died down, we ate the rice, weevils and all.

It took five days to reach Japan. On January 15th, 1942, the ship arrived at the city of Todatsu on the island of Shikoku, the southernmost island in the chain that forms the country of Japan. Because the docks at Todatsu were too small to accommodate the Argentia Maru, she stayed several miles offshore waiting for a transport to pick up the prisoners. A light cold rain fell as we were herded off the ship and onto the transport vessels. We were then marched a short distance to the railroad yard and promptly loaded onto a cargo train.

Twenty minutes later, we disembarked at the station and then we were marched another half mile to a barbed-wire fenced compound. We had arrived at Zentsuji prison camp. Shortly after our arrival, the governor of Guam asked the Japanese for permission to hold a personnel inspection. He was so focused on impressing the Japanese with his authority that he failed to consider our actual situation. We all lined up for the governor’s inspection, but we resented the hell out of him for putting us through such a ridiculous charade. At this point, we were obviously ragged beyond belief, and our morale was at an all-time low. He inspected the lineup, walking back and forth in front of us, and criticizing our filthy clothing and messy hair. Shortly thereafter, he was transferred out of Zentsuji to an unknown destination. And we were all glad to be rid of his pompous ass.

Zentsuji was the first POW camp constructed in mainland Japan and we, along with a handful of Kiwi coast-watchers, were among the first captives to arrive. Throughout the war, thousands of POWs would come through Zentsuji. American, British, Australian, and New Zealand prisoners were all there at one time or another. Zentsuji was also the headquarters and waystation for all POW camps under Japanese rule. Prisoners would be transported to Zentsuji first and subsequently be transferred elsewhere, including many from my original unit.

Contact Me

Get In Touch

Do you have a story you want to share? Maybe an image to add? Contact me today, we are always accepting new historical content to share with future generations.